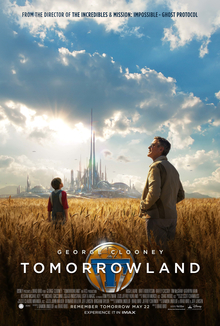

Movie: Tomorrowland

Directed by: Brad Bird

Starring: George Clooney, Hugh Laurie, Britt Robertson

Verdict:

Brad Bird’s aggressively optimistic Sci-fi utopia flick tries hard to dazzle with visions of a possible tomorrow, but while Raffey Cassidy’s performance as Athena simmers alongside the special effects, neither were enough to uplift the film’s horrendous pacing and tragically underwhelming plot to anywhere near its promise.

In depth:

For such an effects-heavy film, Tomorrowland was surprisingly muted in most of its previews, being more focused on building an optimistic vibe and buoyant, hopeful atmosphere, rather than on wowing the audience with special effects. I was initially pleased with this angle, for despite my love of Blade Runner and the rest of the Cyberpunk canon, years of relentlessly bleak and nihilistic dystopian science fiction had ground me low, and while I couldn't stomach a return to the Space Age euphoria of The Jetsons and its relatives, Tomorrowland's exaltation of scientific possibilities as per the previews showed promise in filling a void left in me since Disney’s 2007 animated feature Meet the Robinsons. Unfortunately, the previews went well beyond merely “doing justice” to the movie - they were downright disingenuous. Like the film’s hapless protagonists, I felt duped, deceived by a glossy veneer of thoughtful utopian futurism which turned out to mask a spastic and unwieldy film, with seemingly minimal direction and only a heavy-handed “message,” delivered with all the subtlety of a back alley mugger, to greet me at the end.

Our mournful tale centers around two decidedly different protagonists, both of whom have had their lives altered by contact with the eponymous location. We’re introduced to Frank Walker (Clooney), a bitter and cynical man who is apparently addressing an undisclosed audience about “how we got to here.” The film throws us back to the 1964 World’s Fair, where an eleven-year-old Walker is gearing up to present his homemade “jetpack” to a very bored Hugh Laurie. I’ll admit that this is the first - and sadly, only - hope spot in the entire film; the scenery was bright and colorful, and the quasi-philosophical exchange between the boy-genius and Laurie’s character Nix, though hurried and shallow compared to presentations in other movies, did strike at the story’s main nerve: that the invention of any dream, any idea - however fuzzy or incomplete - may spark the seeds of tomorrow’s innovations, if only by willing the heart to consider possibilities. However, the best part of the beginning was undoubtedly the introduction of Raffey Cassidy as Athena, a young girl with a secret who takes a liking to young Frank and gives him the pin that functions as a pass to Tomorrowland - the hyper-futuristic, creative utopia where all the world’s best minds gather to make the impossible happen. Yes, it’s true that “English little girl” is usually more than enough characterization to stand out in an American production, but in this case she actually has some meat to her. Throughout the beginning and going the full nine yards, Cassidy was one snarky, sardonic, butt-kicking, heart string-pulling fountain after another, and the fact that she’s barely past the puberty gateway only makes her ability to meet most of the expectations placed on her all the more impressive. Her charm and sincerity are all natural, and I wonder what her future has in store for her.

But still, it’s got to be pointed out that Cassidy’s acting chops, even allowing for her age, are only somewhat above adequate, and really only stand out because most of her castmates are sort of a let down. While I usually enjoy Clooney in most of the films he’s in, this time he came up rather short, playing to stock the most conventional kind of curmudgeon-scorned you could possibly imagine. However, the exemplary irritation in the acting department resides squarely with Britt Robertson and her character Casey, the shrill and annoying magnet for most of my frustrations with Tomorrowland. Playing opposite Clooney as the young, bright, and optimistic science enthusiast, Robertson promised to drive the film’s direction, perhaps bringing Clooney out of the dark and setting a good pace for the rest of the movie. Unfortunately, she turned out to be a dud, a quintessential example of character shilling who, while smart, never did much more than shout and have her common sense observations called out as “brilliant.” As with Clooney, her scenes and motivation all amounted to a big “ho-hum,” though I suspect that I probably wouldn’t have noticed as much were I fifteen years younger.

Worse yet, her appearance coincided with where the plot takes a real nosedive...and pretty much stays at low altitude for over 90 percent of the remainder of the movie. Story rot doesn’t even begin to cover it; everything spanning from the time she discovered the Tomorrowland pin, until she actually arrives there, was the most bloated, meandering and drawn out stretch of cinema I’ve seen in the past year. This was supposed to be the point where the plot hits its “meat” - when we learn that not all is sunshine and sprinkles in Tomorrowland, and a contingent of creepy robots are sent to silence Casey from discovering the truth. Unfortunately, we’re treated to a couple of robot fights, a few extended chases, and a lot of fluff and filler. It had its moments, I admit - for example, seeing Frank Walker’s near Batman-levels of prepared ingenuity when the bad guys follow Casey to his home was good fun, and one of the best scenes in the movie. But by and large this hour-long stretch, in an already overly-long 130-minute movie, limped on with little direction, dragging the viewer along while giving no incentive to command our attention other than a sub-adequate jigsaw plot. Of course, piecing together the story’s “puzzle” might have been fun were there anything at the end of the road worth discovering, but alas, no; they don't even arrive in Tomorrowland until the last 30 or so minutes of the movie, after which everything resolves on the words of the villain’s rather illogical 2-minute diatribe, and not even the surprising maturity by which the movie’s message is presented could offset its heavy-handed delivery, or Tomorrowland's many failings in general.

So was there anything good in this movie? Well, aside from Cassidy and her antics, the special effects were great, as to be expected. They were dazzling on their own, but what really stood out was how they dovetailed into the movie’s wider theme of optimism and possibility; the effects, along with the various props accompanying them, had a very “classic” feel, almost as if they were cooked up in the mind of an imaginative ten-year-old - which, when you think about it, may have been the point. Likewise, they weren’t splattered everywhere, giving the viewer new distractions every 3 seconds, but were used economically, mainly to punctuate how this or that event was in some way “amazing” - and to be honest, it usually worked. Too bad that even this concession merely damns by faint praise, since the concentrated usage of special effects only highlighted the absolute barrenness of the rest of the film; the draw of flickering lights or a CGI explosion every minute has been the saving throw of many a sub-par movie, as they at least keep the adrenaline amped and the mind numb. But with no such salvation in Tomorrowland, the long desert between the first and last 20 minutes of the movie where nothing of real substance happened felt that much longer.

It’s easy to sneer at my harsh critique - to call me a tin bully, to chide me for cutting down a movie obviously meant to appeal to children. But that all misses the point; there are many, many, many movies, for children and for adults, that push the same optimistic message of “dream big” with a grace, subtlety, or charm Tomorrowland couldn’t hope to achieve. While it definitely contained within it the seeds of a solid, mature reconstruction of the future utopianism it tried to embody, we will have to wait another day for a film that can bring those seeds to bloom.

Grade: D