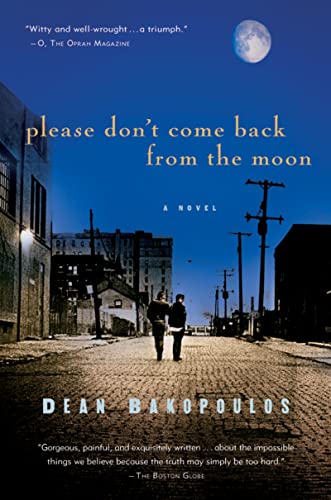

Book: Please Don’t Come Back from the Moon

Author: Dean Bakopoulos

Publisher information: Orlando, Fl: Harvest Books, 2005

Genre: Bildungsroman/Magical realism

Fatherlessness churns and bubbles in the fiction biz, rising to the surface every so often, but few meld the topic with brutal grit, economical prose, and an airy surrealism quite like Dean Bakopoulos in his 2005 debut novel, Please Don’t Come Back from the Moon. Bakopoulos weaves a tale of restlessness and abandonment through the eyes of Michael Smolij and his peers, young boys from a working-class Detroit suburb whose fathers vanish over the course of several weeks with but one hint to their destination: the Moon. As these men slither away from their families, their wives struggle to rebuild in the wreckage while their children, sons especially, try to make sense of the void that now breaks them open. Tailing Michael as he wanders dazedly through adolescence, stumbles into adulthood, and bumbles about the burdensome responsibilities of family and finances hooked readers and critics alike, netting the novelist a few accolades and enough momentum to launch a 2017 film based on the work starring James Franco. But the novel reveals much more than a standard bildungsroman with a few gritty swear words thrown in. In our current, politically charged environment saturated with #metoo agitation and rebellion against perceived gatekeepers to traditional power, it seems easy to dismiss Bakopoulos’s work as an edifice to young, white man-children who know nothing of “real” suffering. But behind the cursing, drinking, and sexual indiscretions lie a piercing examination of the many inescapable spirals that twist our lives on both personal and social scales

Michael, our narrative filter, surveys his increasingly hopeless surroundings with a more discerning eye and expressive vocabulary than most, but don’t think he’s some diamond in the rough. He, his violent cousin Nick, and their peers are ground from the same course flour as the rest of their blue-collar, Eastern European neighborhood, and our protagonist fell into the same pits of vice, vandalism, and compensatory machismo with but a modicum of literary talent and the support of his mother and her second husband to lift him a bit above the tide. Though Bakopoulos displays the rough edges and stilted speech expected of a debut wordsmith, he gives Michael a raw, unfiltered voice that avoids repelling the viewer, while using episodic vignettes of his life - an affair with an older woman, a confrontation with one of his mother’s temporary boyfriends - to explore the sense of loss born out of the fathers’ disappearance. With Michael and his friends caught in cycles of expensive education and low-wage service industry jobs, Bakopoulos captures the sense of listlessness and meaninglessness facing the post-industrial working-class, staring off at the accomplishments of unions past and bitter about their inability to obtain a measure of economic justice in the present.

But the story’s hallmark lies not in its mocking of modern convention, nor in the exploration of fatherlessness. Dig deeper through the tracks of growing pains and hard drinking working-class youths, and you’ll find a sensitive treatment on male struggles with depression and identity, issues still sparse in our supposed cornucopia of literary diversity. This is where the magical realism elements of the story, subtle but artfully inserted, shine through. We never get a definitive answer on whether any of the town’s men actually went to the Moon, with plenty of evidence to the contrary. But Michael, in one of the most sensitive depictions of a man’s uncertain slide into depression I’ve ever read, suddenly finds himself elevated a few inches off the ground while walking the streets at night. Bakopoulos’s succinct prose and narrow focus on Michael’s point of view prevents us from knowing whether or not he’s imaging things, but as the other young men of his generation, all grown and with problems and families of their own, suddenly show up in one location to stare at the Moon, we feel locked under the same spell as they, unsure what will happen next, but anxious to find out. This skillful threading of the mildly fantastic with a visceral modern realism remains the novel’s pièce de résistance, and mounts the suspense on whether Michael will continue to sink through the same muck of depression and meaninglessness that claimed his father.

If Bakopoulos falters anywhere, it’s with the disjointed blending of some elements of the main story arcs. Some of Michael’s misadventures fell neatly into the bildungsroman playbook, giving insight into how his father’s abandonment left his vulnerable to the dark ministrations of others and shaped who he is. But others meander into reckless youth territory, and could have been excised from the novel altogether. But maybe I’m just splitting hairs. Please Don’t Come Back from the Moon weaves a sad, solid, slightly surreal narrative that not only squares with the hopelessness left over from Industrial America’s abandonment of their blue-collar rank and file, but also the subtle ways that depression and listlessness can bore holes into our lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment